- Elizabeth Vocht

- The Air Force

Photo by BBC / YURIY DYACHYSHYN / AFP / Getty Images

In the photo in the collage: a wall made of artificial flowers, installed by the American Foundation in Lviv in memory of the victims of the Russian invasion

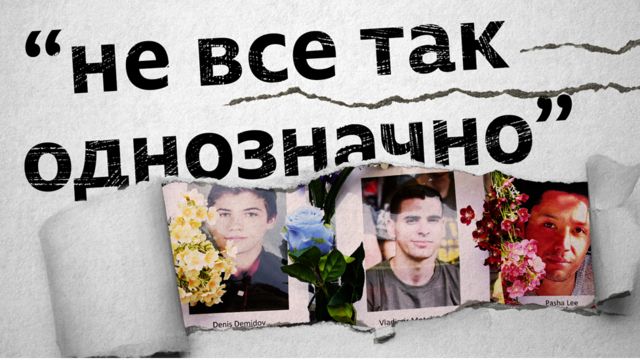

Two months after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, there has been a heated debate in Russian society about how to treat it.

And while the arguments of opponents of the war mostly boil down to the fact that the decision to send troops to a neighboring country was criminal and immoral, those who support the “special operation” justify it in different ways.

Some recall how “NATO bombed Yugoslavia,” others say war was inevitable, and no one knows the truth about it, and still others ask questions in the spirit of “where you were for eight years while people were dying in Donbas.”

The BBC spoke with Oleksandra Arkhipova, a social anthropologist and author of the (Un) Interesting Anthropology telegram, about the Russians’ attempts to justify Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and where they come from.

BBC : Why did you decide to study the arguments that people use to somehow rationalize the war in Ukraine? In your post, you call them justifiable and protective clichés.

Oleksandra Arkhipova: People don’t just discuss the world around them and their attitude to it – they create their own world. That is why now in the language of people, both orally and online, there are so many identical phrases. We call them clichés – for example, “not everything is so clear.”

Repeating these clichés allows you to create the feeling that there are many people who think alike. And when people want to join the majority (and this is a human trait – we all really want to be part of the group), they start using clichés, which they think the majority speaks.

At the same time, of course, the native speaker may not feel these phrases as a cliché.

That is why my colleague from America, Gulnaz Sharafutdinova, and I have compiled a dictionary of clichés from Russian conversations about the war, which are repeated many times – at least a thousand times.

I’m not talking about clichés that show an anti-war stance – there are many.

For example, despite all the repression and persecution under Article [20.3.3 of the Administrative Code], the number of people who write on Russian social networks “no to war” and “I am against war” is extremely high.

In our work, we collect clichés that defend or justify the very fact of war. As disgusting as it may sound, it is important for us to understand how the justifying “Russian language world” is created.

BBC : How does your search work?

OA: We find a number of statements, then we look at which phrases are repeated, then I run a search for variants of this phrase. For example, “Don’t you feel sorry for the children of Donbass?” Or another option: “Don’t you feel sorry for the children of Donbass?”

Next, I look at how many texts fall on such a cliché, and already assess their popularity.

My colleague and I divided these clichés into four main blocks. There is a bloc that we tentatively call: “And in America, blacks are lynched.” These include statements such as “and Biden started the war”, “America bombed Yugoslavia”, “Mariupol is in the teens of NATO missiles”, “if it weren’t for us, there would be more victims of the war”, “and where have you been for eight years” ? ”

Photo by BBC / Anastasia Vlasova / Getty Images

In the photo in the collage: a destroyed residential area in Borodyanka, Ukraine. April 5, 2022

Our language is our main traitor. She gives us our basic guidelines. And it follows from these clichés that the main enemy is America, not Ukraine.

This partially removes the wild paradox, according to which, on the one hand, many Russians support the war, a “special operation” in Ukraine, and on the other hand, consider Ukrainians a fraternal people.

BBC : This argument is often called “Votebautism” (from the English what about …?, “What about…?”, a rhetorical device aimed at distracting attention from an unpleasant question by criticizing the opponent. – Ed .). This is a popular tool of Russian propaganda: for example, Vladimir Putin, when asked about torture in Russian prisons, says that “there are no less problems in other countries.” Why is this argument so common in Russian culture?

OA : Because it is much easier to point out the enemy than to explain one’s own actions. It mobilizes, it is a trick that takes away your responsibility and demonizes the enemy. In a sense, this is the rhetoric of a small child.

When a child is asked why she hit Petrik, she says, “And Petrik started first.” “Why did you steal in kindergarten?” – “Because everyone steals.”

When a child is not ready to think about his own responsibility for what is happening, he refers to the current state of affairs, where there are strong people who do the same, and he is in solidarity with them.

And here: in answer to any question we are told that somewhere is even worse.

BBC : What other blocks have you identified with a colleague?

AA : The next block is “My country, right or wrong”. “I justify Russia not doing it there.” These include quotes from actor Sergei Bodrov that “during the war you can not talk bad about their own”, “do not give up”, “Russia does not start a war, but ends them”, “Russia always saves everyone”, “we are just historical do not like”.

These are expressions in which we either idealize Russia or acknowledge that there are problems, but we must be loyal.

Photo by BBC / Andre Luis Alves / Anadolu Agency / Getty Images

In the photo in the collage: view of Yalovshchina Park, turned into a cemetery for war victims in Chernihiv, Ukraine, April 13, 2022. At least 700 people have been killed in Russian attacks in the city, and shelling around the main cemetery has had to be buried elsewhere.

I call the third group “I’m a little man.” These are arguments in the spirit of “what can we do”, “we are small people, they know what to do there”, “there are no fools sitting there, they know what they are saying”, “nothing depends on us”.

BBC : Why are clichés of this type so common?

OA : Russia is very apolitical, and it has become so thanks to the conscious support of “learned political helplessness.”

We have done everything to ensure that people do not take any active political action – and preferably do not even go to the polls, but rather go to the country instead.

In a situation of war, this position of non-interference (“what can we do?”) Must be justified. And the position of non-interference is justified by underestimating one’s own importance and destroying subjectivity, if you want: “we are small people”.

That is, the position can be expressed by referring to the messianic role of Russia and the a priori hostile West, when a person says: “We are simply not historically loved, we will be attacked tomorrow by Biden” (these are aggressive clichés).

Or you can, on the contrary, diminish your influence and portray yourself as a being who can not influence anything, and thus removes guilt. Guilt for bombing Mariupol, for the murders in Bucha. After all, he “can not influence anything.”

BBC : What belongs to the fourth group of clichés that you singled out?

OA : I call the fourth group “After Truth” or “Denial of Facts”. These include arguments in the spirit of “no one knows the whole truth”, “time will tell who was right”, “history will put everything in its place”, “they are bombing themselves” and so on.

Photo by BBC / Carolyn Cole / Getty Images

In the photo in a collage: in the cemetery in Irpen, Ukraine. Marina is holding a photo of her father, 63-year-old Mykola Honcharenko, who died when Russian forces fired on his car. April, 2022

BBC : Journalists are often confronted with this category in their work. Don’t you think that it exists, in part due to the fact that during these months and wars the meaning of the word “fake” has been devalued, and so now they mean any unpleasant information?

AA : We wrote an article earlier this year called The Ministry of Truth about government fact-checking projects. The state has adopted the word “fake”, many Kremlin channels use this logic to “check” fakes: “This is a fake, because the Ministry of X said otherwise.”

In fact, no fact-checking is happening. The word “fake” really devalued. It is now called any information that does not match the official.

This trend did not appear now, but in 2020. We now have five fake news laws. In 2020, I often said that these were very scary articles, but everyone was cool about it. In fact, the development of this trend has led to what we have now.

My colleagues and I studied about 350 cases of people who were punished in 2020-2021 under criminal and administrative articles for “fakes” related to covid.

And it is clear that more than 75% of cases have nothing to do with what we call fake news, rumors and conspiracy theories. There are units of such cases.

75% of administrative and criminal cases for “fake” allegations are statements that disgrace the activities of local institutions or cast doubt on the actions of the authorities.

For example, the case in Irkutsk about a message on Viber like: “Girls, do not go to work, I heard that the chief physician fell ill with covid and goes to work, but we are not informed.” That is, the authorities seem to be hiding information and allowing infection.

People were accused if they doubted the government’s decisions or ability to cope with the code. That is, even then they developed a rule according to which false information is called fake from the point of view of power structures.

Currently, this trend is developing right before our eyes (we are making such a database). On March 4, the administrative law was passed 20.3.3. about discrediting the Russian armed forces, and as a result more than 1,300 people were fined for a poster, a phrase, a badge on a bag, blue jeans and a yellow jacket, for a blank sheet of paper, Orwell’s book and “no war” on the avatar.

There is a criminal article for fakes about the Russian army, which continues to develop the logic of punishment for fakes from 2020.

We now have 32 criminal cases under the new article for “fakes” about the armed forces and the “special operation” that have been opened in the last month. It’s a lot.

The case of artist Sasha Skolichenko from St. Petersburg, who is accused of creating a counter-message, has been heard – she posted information about the deaths in Mariupol next to the price tags in the store.

But most of the cases under this article about “fakes” are the same as attempts to break the information blockade. These are publications of videos from Mariupol, stories about the crimes of Russian soldiers, support for Ukraine, anti-war statements. All this is considered “fakes”.

BBC : But it can’t help but affect people’s opinions? Because if the limit of “fake” is so blurred, then how to really say where the truth is? Even people who reflect can find it difficult to understand.

OA : Yes, and in fact in this case the government finds itself in a win-win situation. Because the person on whom a lot of information is dumped does not believe and considers the murders in Bucha a fake. Or he simply despairs of trying to understand and says that “we will never know the whole truth,” and withdraws from analysis. And then the official opinion also wins.

That is, the task is not just to make people believe in one way or another.

For example, we know that the truth is conditionally “A”. The task of Russian propaganda is not only to make us believe that the truth is “B”, but also to make people withdraw from the process and not believe in “A” or “B”. This is also good for the government.

BBC : Why are the clichés we are talking about forming and attracting so many people now ?

OA : The general effect we are talking about now is called collective avoidance. He is widely known. Collective avoidance occurs when people are confronted with information that threatens to destroy the unity of the group.

In our case, the very recognition of the fact of war – not just targeted strikes, but large-scale ground operations, in which not individual militants are killed, but civilians are killed en masse – threatens the integrity of Russian society.

That is why Russian society is fighting this as hard as it can.

BBC : And why against this “collective avoidance” you are talking about, did not all the attitudes with which generations grew up work: “so that there is no war”, “war is the worst thing that can happen?”

OA : There is a really strong fear of war in Russia.

But the war in the Russian imagination – this is what comes to your doorstep. This is when your father goes to war, when foreign soldiers come to the house, when the house is burned, when the children are in danger, when there is a famine. This is war.

And now people are taking a convenient position, as official Russian opinion tells them, and supporting the clichés we are talking about.

At the same time, if their relatives, friends, children send them photos of bombed-out houses, photos from Bucha, the acceptance of this fact contradicts what is said on TV screens. And here there is a great threat of cognitive dissonance.

Therefore, the human brain is ready to do anything to avoid this dissonance. Especially the brain of a conformist person – and the Russian population in general is very conformist.

As a result, the brain repels inconvenient information – for example, that people are actually being killed in Ukraine. There may be the opposite situation: a person is completely immersed in the war in Ukraine, and any facts about charity will repel him.

BBC : Let’s explain what conformity is.

OA : Conformity is a person’s tendency to show solidarity with the opinion of others, with those whom he considers an important majority. A conformist person will never say, “I am against it.” She will agree with what others say, even if she internally thinks they are wrong.

I recently had an experiment here that fascinated me. The authors of the article recruited people to interview those who support Vladimir Putin and asked them how they feel about him.

But the wording for different groups was different – one group was simply asked about Putin’s attitude, another group was asked with a preamble that two-thirds of citizens support Putin, and a third with a preamble that only two-thirds of citizens support Putin.

As a result, those who received the wording “only” dropped their support for Putin.

Let’s put it this way: in authoritarian regimes, such as Russia, the government is trying to wean people from expressing political opinion.

But it has interesting consequences. They are that in such regimes, people who have been weaned from political action express sympathy not on the basis of any real preferences, but on the basis of associating themselves with the majority.

If the majority thinks they support the president, then I will say that I will support the president. And if I see that the president is not supported by many people, then maybe I will not.

In other words, I am sure that at a time when the political situation in Russia will change dramatically, there will be a huge number of people who will say that they never supported the Russian government in 2022. There will be a huge number of people who have “always been against”.

BBC : In our talk on vaccination conspiracy, you said that people in Russia trust those around them more – for example, the conditional “neighbor’s sister” than the institutions and the state itself. Russia has a huge number of social ties with Ukraine. But now Russians often don’t even trust their own children or close relatives who tell them about the horrors of war, but they do believe what they say on TV. Why is this happening?

OA : It’s really happening. And this contradicts what we know. It is really strange: why a year ago the Russians referred to Maria Ivanovna, whose sister’s sister died of vaccination, and today this mechanism works exactly the opposite, and we do not believe what our close friends and relatives told us?

There is a very important thing here. When a person says that vaccination is dangerous because “a neighbor’s sister told how the girl died from vaccination,” in fact, her opinion is already formed.

The story of the neighbor’s sister is only an outward confirmation of what the person believes. She understands that if she says she “just thinks so”, she will be stoned. That is, we need an imaginary majority with which a person is in solidarity and whose voice he becomes.

But in the situation of war we are discussing now, the fear of cognitive dissonance seems to be much stronger – even for family ties. People resist with all their might and say, “That’s not true.”

Photo by BBC / Maxym Marusenko / Getty Images

In the photo in the collage: civilian vehicles destroyed during the Russian invasion of Ukraine and collected on the outskirts of Irpin, Ukraine, April 18, 2022

There are many such stories. I am now friends with a wonderful artist, her family fled from Kharkiv.

The man stayed there. And they are in despair, because the man’s parents, who are in the Crimea, do not trust them. They say, “Nothing, you will be released soon, be patient.”

That is, we see the opposite effect: here the imaginary majority with which parents want to show solidarity are those who believe that there is no war, but there is some unpleasant operation in Donbass.

And to avoid cognitive dissonance, the brain rejects any other information – including from relatives.

BBC : Are there any positive examples of resistance to this majority?

OA : Culture is able to create mechanisms for the protection of society, even in a situation that seems to us completely hopeless. They come from where they often did not expect. For example, the rapid rise of anti-war graffiti. Graffiti is probably too narrow a word: various inscriptions in public spaces.

People leave a huge number of signs on the porches, in elevators, at bus stops, on bulletin boards. They are being persecuted for this, and now there are many criminal and administrative cases related to graffiti. But still less than these inscriptions.

Today I talked to a girl who made such graffiti. These people have a great desire to break the information blockade. Of course, such inscriptions will not be able to stop the war, killing people right now. But they can break the blockade.

It is very important to show people that there is no imaginary majority.

It is important that the word “war” be in the public space. That the person saw that many people leave such inscriptions, and understood that there are many people who do not agree with “party policy”.

This is an attempt to explain to the imaginary majority that it is not really the majority.

Want to get top news in Messenger? Subscribe to our Telegram or Viber !